A new labor race to the bottom?

Our policies about people need attention before we completely dehumanize ourselves.

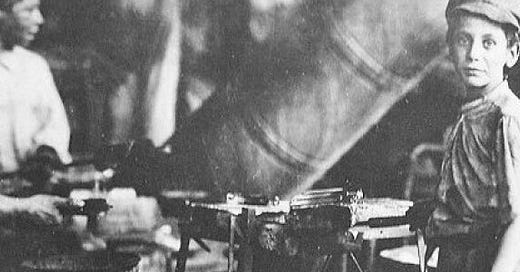

Our American economy began with a massive block of free labor in the form of enslaved people predominantly in agriculture artificially depressing the overall cost of the labor market, skewing our collective cultural understanding of expected costs, and anchoring problematically unrealistic expectations of profit and growth. While the industrialization of labor has shifted those experiences into more acceptable forms of exploitation (offshoring, child labor) our cultural expectations remain rooted in the expectations our economy was founded on. These expectations show up as assumptions about cheap food, about anticipated profits, understanding of full-time work, and a bunch of other concepts that all drive us toward a painful habit of dehumanization in the name of efficiency and growth. Connecting this cultural-economic history to America’s deep-seated racism and the painful futurelessness of modern working class white communities, and we have a deeply problematic combination that is driving a new commitment to expanding child labor.

Over the last few months, several state laws across the country (see here, here, here, and here) have loosened restrictions on young people working in dangerous conditions. Often wrapped in some rhetorical combination of liberty, self-determination, and parents’ rights, the end result of these regulatory changes is more children working in dangerous conditions with less oversight. A question we need to be asking is why now? Why would we be intentionally going backward on protecting children now? These laws are being passed in places struggling to expand labor supply in a labor market near capacity and in communities deeply suspicious of immigration having been fed stories of immigrants stealing jobs for more than a generation and refugees having bought too deeply into the narratives of the “global war on terror”. One thing all these laws have in common is the cultural intersections they have emerged in and the attitude toward how we value people implicit in our culture relative to work.

There is a whole set of people policies (more to come here on each one) that should be animated by consistent, shared principles but that tend to diverge from a values perspective based on the politics of the narrow issue spaces in which they emerge. Labor, immigration, refugees, parental leave, wages — each rooted in how we think about the definition of “American” and how we think about the value of humans especially relative to other things we consider important like achievement, opportunity, and wealth. Broader definitions might invite more capacity but also more creativity about how we work together and on what and how. How those definitions overlap and diverge are a part of the same picture painted by the consequences of immigration, refugee policy, wages, and rest. Capitalism will consume whatever labor we are willing to give it — our economy is designed to consume humans, so why not feed it our children, too? (There’s a Jonathan Swift reference here somewhere — suggesting, perhaps, that we’ve been wrestling with this exact question since at least the 18th Century.) Perhaps we might want to reconsider what limits matter to us and what we’re really optimizing society (and the economy that supports it) for.

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support this work. Subscribing to 7 Bridges is the best way to keep it free and open to all.