A real solution buried in a War Game

The most important insight might not be anything that happens in the simulated Situation Room but what kept one of the characters from ending up on the wrong side of the "war".

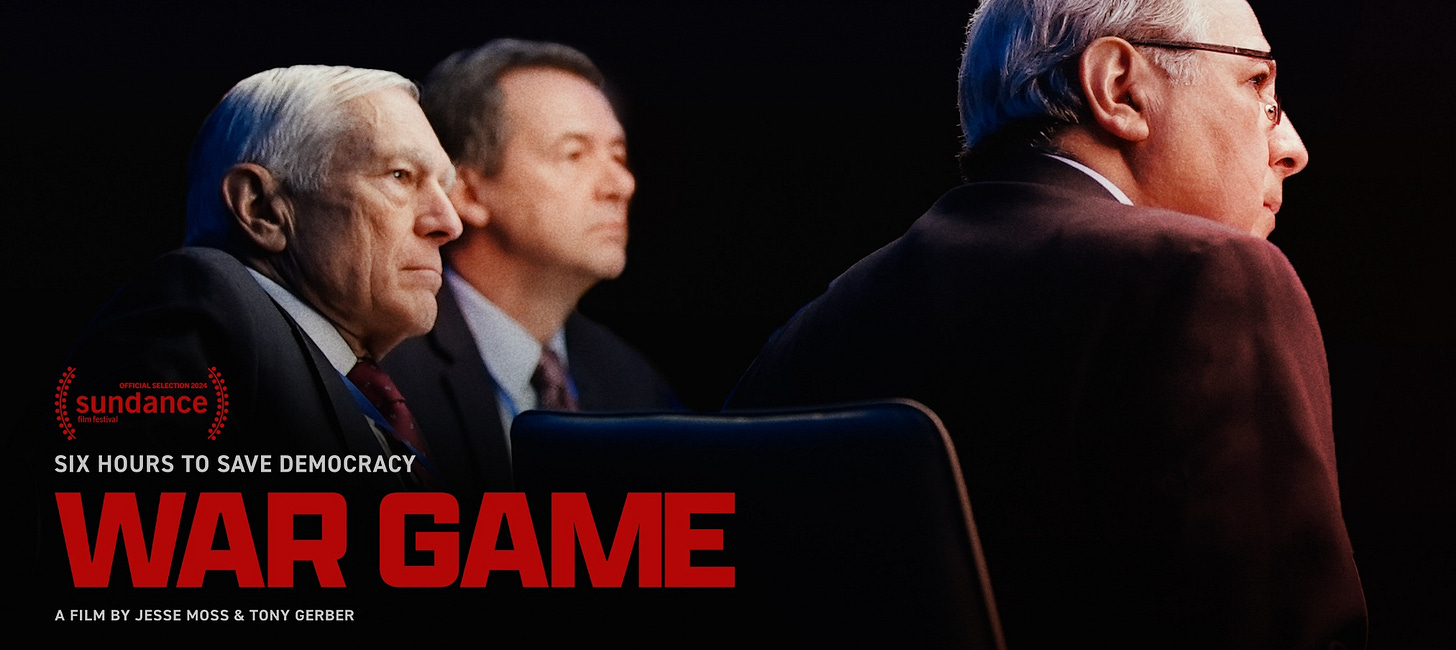

Last weekend, I had the opportunity to host a screening at my local Upstate Films of a new documentary called War Game that is built around a tabletop simulation exercise of how the U.S. government might react on January 6, 2025 if similar unrest occurs to 2021 — but this time includes support from within active duty military national guard units. The subject matter is urgent and disturbing and to process demands the opportunity to immediately process the experience and the content. I wrote a pretty damning essay last spring about the feature film Civil War released by A24 with seemingly no regard for what graphic depictions of political violence might do without context in our culture at this moment without that kind of discussion and experience. In a moment of extreme political intensity and uncertainty, this kind of dialog is difficult, disturbing, and utterly essential. Hosting the discussion that I believed was lacking last spring felt like a “put my money where my mouth was” kind of moment, and I hope for the small group of community members in my small town who participated that it felt like the opportunity to examine and discuss needed to transalte the stressful and unsettling experience of the film into something like new perspective, new thinking about what elements of our democracy and our democratic culture we might can lean into, revinvest in, and strengthen despite our own uncertainties and fears.

In the film, a number of veterans describe their own experiences in the military with fellow servicemembers who might have come into the military with existing extreme views or who teetered on the verge of radicalization both as a result of the disenchantment of their service experiences and the deep failures of their post-service veteran experiences to sufficiently and effectively care for them. One of these participants who leads the Red Team in the scenario is a US Army veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom named Kristopher Goldsmith. Perhaps the most important unasked and unanswered question in the entire film — in terms of our ability to intervene along the radicalization paths that too many Americans are on — emerges as he tells his personal story.

Kris describes in painful detail his disenchantment at fighting in an unjust war, his battles with post-traumatic stress and suicide, and his own teetering on the verge of radicalization. What we don’t see is what or who intervened to put him on this path of fighting for democracy rather than finding himself deep in the radicalized right-wing of American politics. He mentioned the role of years of therapy as fundamental to his recovery, but what got him there? I suspect there was a moment, a person that offered an off ramp at a moment he was able to accept. What was that offer? Who was that? What was that voice? What was that better, truer story? Can we examine that moment, that intervention and use it to design how we might create similar opportunities for our friends and neighbors who might find themselves similarly teetering on the verge of information landscapes and stories of perceived or actual grievances, of deep frustration and disenchantment on the edge of radicalization that they can’t interrupt for themselves? Regardless of our philosophical differences, our policy arguments, our deep-seeded cultural differences, we might be able to keep them in our collective, healthy civic life, committed to the rule of law and the power and value of pluralism to build a more creative society, to keep them in a healthy vibrant democratic culture, to keep them active in our communities with a sense of togetherness and belonging rather than turning to the fringes of a violent underculturre for those same things but mutated in their morality in a pernicious, misanthropic cult that is eroding our democracy and endangering our civic life.

The documentary paints a vivid picture of one potential risk of extremism and internal threats to American democracy, and I recommend finding a screening or streaming it later this month. It does not take time to unpack all the dimensions that underlie that extremism or shape our civic dysfunction — and to be fair could not in a single 90-minute film. But many of them are actively on display: from rigid, aging governance structures to unhealthy information systems to weak intercommunity connections and shared experiences to strained social cohesion and weakened pillars of democratic culture. Each of these dysfunctions could have its own documentary treatment, and each demand sustained efforts to get us past the diagnosis and into the realm of the cures and the ambition that might could get us into the better, truer stories of a better future we crave. AND while we're here in this complicated and difficult present, we ought to spend some time — if we can slow down the fear and uncertainty that this movie elicits — to unpack just what off ramps to radicalization we can offer and invest in, to clarify the experiences that helped Goldsmith make this film rather than be its subject. Those investments, those experiences might could make our current state of civic life less uncertain and less dangerous as we reach for that better future.