Weekend Edition: Places, not maps

Modern life is full of abstractions -- many of which expand our lives in meaningful ways. But finding opportunities to experience "places" directly helps us embrace and expand our humanity.

In the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, a strong narrative is developing about how, for the first time, Putin is losing the disinformation war. The Biden Administration has done such an incredible job rapidly declassifying and releasing intelligence ahead of Putin’s moves that they have managed to undermine Putin’s ability to dissemble, obfuscate, and outright lie about reality more effectively than ever. And because of his inability to manufacture reality, to craft his own version of events, Putin is actually failing. And while much of that narrative about information and story feels exactly accurate, none of it has stopped Putin from invading another country and killing thousands of civilians. Millions of people are running scared, and thousands of others picking up arms to stand and fight right now, in this moment.

Narrative matters and limiting his ability to control it may limit Putin’s capacity to maintain his stranglehold on his own people in particular. The invasion may be harder for him to execute, more uniformly opposed by the West than anyone expected. But it has not been stopped and is, in fact, continuing to accelerate with thousands of civilians dead and millions displaced.

At the same time the Biden Administration and the West are uniformly opposing and standing against Putin and winning the information war today — the invasion is still happening to the people of Ukraine. (And that Putin has not been meaningfully restricted by outside forces and the Western narrative is that he must escalate to find a way out may be a hint that he could be winning afterall…) This is not an either-or, which-matters-more moment. Both matter. Both conflicts need to be won. But behind our layers of abstraction of media and story and narrative, behind the stereotype and livestream, behind the maps we use to order and organize modern life, we cannot allow ourselves to lose track of the places they represent.

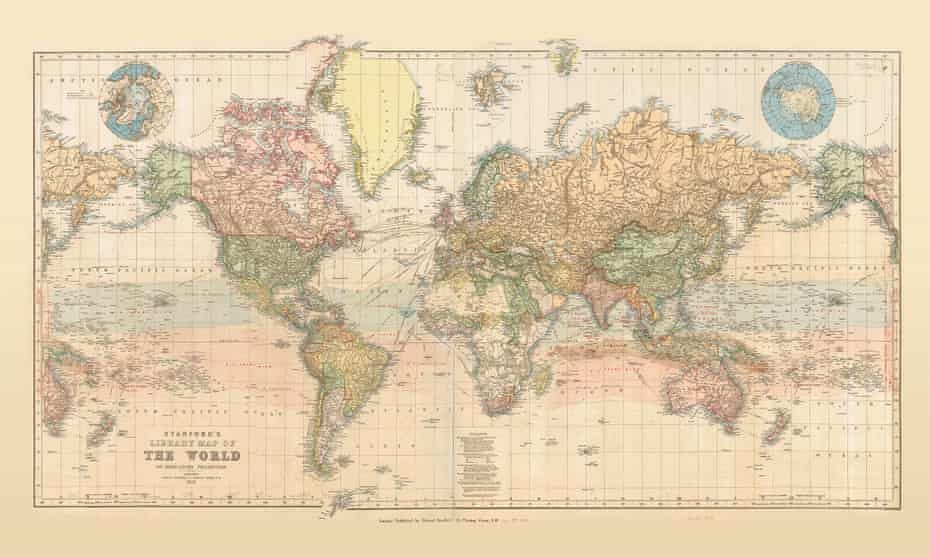

Part of the power of innovation and especially technology is its offer of both simplicity and capability: the ability to enable us to do things we could never do without tools without the requirement that we fully understand them. But after several generations of innovation and our co-evolution with modern technologies, our society, our entire experience of reality rests on layers upon layers of innovation, all of which represent abstractions that each create some small distance from our understanding and direct experience of reality. (Warning: Lacan and Foucault ahead.) And as we are more and more dependent on them for our daily lives to function, the abstractions feel more and more important. More and more the maps of reality feel more important, more real than the places. Layer upon layers of abstraction, stacked on top of each other years after years until we struggle to distinguish between the experience and the abstraction.

We no longer consistently or effectively distinguish between the map and the place.

After a century of unparalleled technological innovation but also expanding complexity of our community structures and political economy, our experience of the world rests on top of layers upon layers of abstraction that each of us misunderstands incompletely leaving us in a fragile dependence but incapable of inspecting that dependence or even recognizing it. We can’t tell the difference between the image and reality, the stereotype and the person, the feeling and the analysis. And now that those layers have built such a fragile distance between us and reality, the meta and the direct have been so interchanged that we often believe that the meta matters more — like winning the information war in Ukraine means that Putin’s invasion has failed despite his ongoing terrorization of another sovereign nation.

This is not about letting go of maps. Maps are useful. They help us manage complexity by giving us order and organizing more information than we can easily hold in our minds on our own. But they are not places. We need both. And right now, in the multi-dimensional crises society is facing, we need to lean in to the places we’ve lost touch with especially the people in our lives we deal with as stereotype and abstraction. The people we touch and bump up against in the dark of the cave while consumed by the stories of the shadows. On the road from New York to Utah to Texas, I have been in dozens of small, rural communities all across the country this past month. The conversations have been fascinating. The people welcoming and kind. And their worldviews, deeply, fundamentally different than mine. None of them have fit the myopic stereotypes of modern politics. These are the people growing our food and building our machines (at least the ones built in this country). They are our long-distance neighbors, and we need them. They are not just the social media representations of their worldviews. They may seem easy to ignore — out of sight, out of mind (like other “other” communities mainstream America has preferred not to engage with) — easy to imagine they don’t matter or might just go away. From the comforting abstraction of urban, elite, liberal communities, “they” are off the map that represents our day-to-day lives, and so we have forgotten the places. But they are part of the “us” that is our imperfect America whether the metadialog suggests otherwise or outright blames them for our pain and uncertainty or not. And our interdependence demands that we make room for the people even if we cannot (and in some extreme cases absolutely should not) countenance their worldviews. Go talk to them. Go see the places. Remember the blood and muscle and complexity behind the stereotype, behind the metanarratives of American politics. It will shake the comforting, inaccurate certainties of the “everyone thinks…” or “everyone sees…” simplicity that makes engaging with the world as it is impossible in favor of a more uncomfortable nuance that makes participation and community more demanding but possible.

And when we seek to understand the complex and the far-away like the invasion in Ukraine, we also need to remember to distinguish between the place and the map, the real and the meta. Both have power and shape reality. Yes, Putin is losing the information war. And yes, people are still suffering. But just because we cannot easily access the place, that distance should not allows us to forget or discount the actual happening over the analysis or the story. In fact, the opposite: it should encourage us to seek out the place with empathy and compassion, to remember events being reported on and analyzed are happening to people. Both are powerful but only one, only the “place” is literal and real. And that while that literal and cognitive distance might be comforting, it doesn't differentiate us from them.

That distance is a way of othering, but “other” is a trap, another abstraction — a way of dissembling, of avoiding the painful reality of our fellow humans, of obfuscating our connections and dependencies on other people we’d rather, in our purity and self-centeredness, not need. And it makes it easy to oversimplify, to live in a comforting but inaccurate disassociation that makes real connection and community harder, that makes solving problems harder, that makes America more dysfunctional because our definition of “us” gets too narrow to fit our messy, complex neighbors. Identity matters and differentiation and individualization are essential to feeling safe and whole and free. But more contact with more “places” will help us embrace the nuance and complexity all around us. They will challenge us, but that dose of reality, that crack in the stereotype and certainty of blanket dismissal will also make progress begin to feel possible again.