Weekend Edition: They cannot be shamed

History, culture, suffering, and how we might begin to find our way to a safer, freer future.

America was heavier for me this past week than at any point since mid-2020 when George Floyd was murdered at the height of the initial COVID lockdowns. With a relentless stream of dysfunction and outright atrocity, all shocking (but somehow not surprising), painful, and traumatic, it feels impossible to predict what will break through. Nineteen elementary school children massacred in their classroom along with two of their teachers within a week of ten people gunned down while shopping for groceries rattled me. I am still having a hard time thinking clearly, helping answer friends asking what should we do, drawing some coherence from my thoughts and frustration and anger.

Helping to organize a student gun control march when I was in high school was the first political activism I ever engaged in, so I’ve been thinking and writing about gun culture, gun violence, and the Second Amendment for a long time. But I have struggled to find something to add to the cacophony of outrage and frustration this week that might be new or useful. I’m not certain this is either (sadly but not surprisingly, I wrote about much of this a year ago), but I’ll offer three thoughts I’ve been wrestling with over the last ten days that fit together but don’t really flow together into a single perspective.

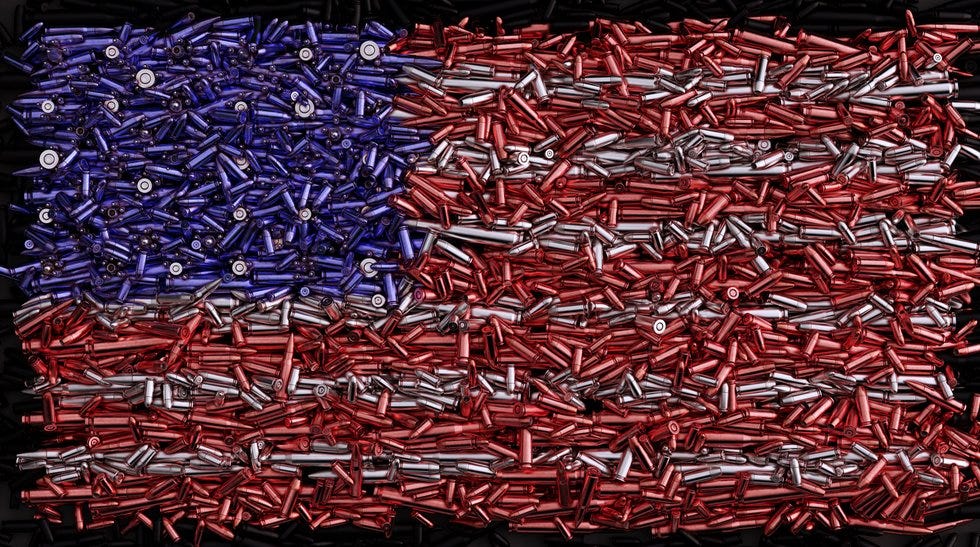

As a start, despite the sense of inevitability that is hard to shake, we must hold on to a simple truth: these violent events are not naturally occurring phenomena. We are not dealing with gravity or natural disasters. These atrocities are the consequences of the society we have designed based on the the principles we have prioritized, the decisions we have made, and the practices we have codified — not the human nature we share. These events are not random. They are not inevitable. And they are not simply evil. They are who we collectively are even if we individually find them repellent. They are America. And it serves no one to hide behind “human nature” or “toothpaste out of the tube” nonsense: our national mythologies and priorities make these things happen.

How America is going is rooted in how America started

The authors of the Constitution were careful with language. The Bill of Rights in particular was wrestled with, debated, and crafted with attention to both intended and unintended consequences. If the founders had wanted to codify an unrestricted, individual right to bear arms, they would have. Despite some strange punctuation, they did not. Instead, they codified a carefully limited and conditional right to bear arms.

The right and the necessity to express hard power as a feature of citizenship found expression in the Second Amendment to address two needs of a young, fragile nation: the ability of a new state, unable to afford a standing army, to raise effective state militia quickly if needed, and for its citizens (at the time, only landed white men) to protect their personal property. One collective and one individual need. Much of our Constitution centers on negative rights and property rights expressly because of who drafted it and is, therefore, inherently rooted in their whiteness and masculinity. Landed white men asserting and enshrining independence from a universally sovereign monarch demanded that they be able to protect the property they claimed ownership over for the first time. And they believed that state-sanctioned violence, either in the form of making war or suppressing perceived (or actual) threats from non-citizens, was an existential necessity that must be kept in the hands of the people. But in a safe, free, modern society, with broad citizenship, with no militia function, hard power can and should be a constrained feature of the state, not something imposed by one citizen over another.

Our nation was designed as a system of semi-democratic, minority rule with political rights dramatically constrained to the landed white men who founded it. The nation has become more democratic over time — often against the will and efforts of the privileged and the entitled who sought to retain their control over it — but remains fundamentally a minority-rule republic. (Given participation rates, even Presidents are selected by barely more than a third of Americans.) The core principles that make for healthy democratic culture are under profound pressure in America to the point of undermining the legitimacy of our project of self-government. Participatory, deliberative, egalitarian, majoritarian — each of these principles has been limited and restricted, and each has been diminished over the last several decades.

At our founding, these principles were deeply present in theory and largely absent in practice. In place of them, founders protected what they needed protected and armed themselves with the tools they needed to protect themselves and their control while taking many of the positive rights people who were originally non-citizens rely on for inclusion, political power, and access for granted. In a society of universal suffrage and broad expression of political rights, the state implicitly promises to ensure the safety necessary to express those political rights in practice. In fits and starts, the nation has moved in the direction of our best intentions and principles. Expanding political power, examining the types of power needed and available to citizens. Too slowly expanding citizenship itself. America has gotten better at democracy as we have grown and matured as a nation — and we desperately need to keep getting better. And part of getting better is examining how our shared moral obligation and responsibility to protect others and how our understanding of what safety means must evolve with the inclusion and enfranchisement of more and more people.

Liberty requires safety

Liberty — the legally protected freedom to live a self-determined life — without safety is not liberty. If society does not protect you enough to express that theoretical freedom, you do not have liberty in practice. The turning away from our collective moral obligation to each other, the commitment to ensure each other’s safety, the safety required for creative self-determination is a dangerous consequence of an empty individualism endemic in American mythology. And it represents an actual conflict of visions between people who believe in and accept their obligation to each other and people who do not.

If you believe that each of us is on our own or buy in deeply to the idea of self-reliance and that the world is dark and scary and most people in it are potential threats then continuing to prioritize your right to arm yourself over almost any other right (regardless of whether it actually makes you safer) makes some sense. Safety is something personally, rather than collectively, guaranteed. But it is deeply inconsistent with the idea that America as a set of democratic structures meant to enable our shared thriving, with being in community and society with one another. And it is also inconsistent with our growth as a nation, the state of the modern state, and our experience of modern life to assume a) everyone can protect themselves; b) everyone should protect themselves; and c) that we don’t share a moral obligation to protect each other.

This failing to recognize safety as a collective responsibility is consequence of and consistent with a privileged, entitled, unexamined adherence to the idea of “individual responsibility” to simply push this responsibility all the way down to children via live shooter drills, to make them responsible for protecting themselves. Arming children will be the end point of that progression. It is the gun culture version of “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” — help yourself, no matter who you are. In either case, too many of our leaders believe they are empowering personal liberty by not intervening. Importantly, for people who do believe that we are responsible for each other and especially for children, that idea may seem patently absurd. But for those who don’t, it is a necessity. There have been too many dark-humored jokes this week about the absurdity of “good guys with guns is the answer to bad guys with guns.” Way too much “obviously this must be enough to make them willing to change.” If they believe the world is dark and scary and they are not willing to accept a moral obligation to protect you, this is their best idea. This is them doing their best. This is in fact the very most they want to do.

We need a new strategy

Back to this week: two dimensions to the ongoing conversation about guns, guns culture, gun violence, and mass shooting need to be pulled to the forefront.

First, if you aren’t doing something wrong, you don’t feel guilty. If you are doing something right and are rewarded for it, you feel the opposite, you feel validated, emboldened, successful. If you’re not doing something wrong, you aren’t breaking any norms or values. If you’re doing not only a right thing but the right thing and you get overwhelmingly positive cultural reinforcement of your self-righteousness from the community you’re actually connected to you never feel guilty internally in the first place.

Shame is a form of internalized community condemnation for violating shared norms and values. If you don't share community with your opponents, you cannot shame them. You cannot shame people who don't care about you or what you think. Shame doesn’t show up when you violate someone else’s values. Your judgment doesn’t matter to them, and their community supports their self-righteousness. So what Republicans and gun advocates feel is actually the opposite of what we would expect someone standing in the way of protecting children should feel. They feel validated, empowered, and emboldened by their success protecting a narrow, mythological idea so they retrench, they push further. Making us a more violent and more heavily armed society where the privileged remain protected and everyone else is less and less safe and therefore less and less free.

The same collapse of trust, failed moral obligation, and narrow, false liberty applies to their entire worldwiew from trickle-down economics to market-based public goods. It is all the same abdication of a willingness to accept the basic responsibility for being members of a community. We are citizens in a system of shared and borrowed power. But to pleas to help, to share the pain of community members suffering, they say, “Not my community. I will be fine — your suffering, your safety are your own.” How terrible to live in that small, mean place under constant threat and in constant fear of a dark and dangerous world completely cut off from even the possibility that other people might be a source of strength and creativity, that they might have as much kindness and generosity to give and to share as you do.

Second, getting better at democracy requires an attention to the trauma we are collectively and individually suffering and the scar tissue it has created in our perspective and habits. Allowing our nation to be led by the suffering of seeing the world as dark and dangerous will only lead us to dark and dangerous places. Getting better at democracy requires a reckoning with the principles we have been prioritizing and mythologizing and a recommitment to the principles that will make our society more creative, more just, more optimistic. Safety is required for the liberty needed to live a life of self-realization and self-determination — safety de facto and safety de jura. Those whom can take safety for granted because they either have the privilege of it or are willing to hide comfortably in the myth of self-reliance can prioritize freedom over safety because they have a version of both. “I can take care of myself, so you should take care of yourself.” But they are blind to the reality that they can take care of themselves partially because society protects them. And here is where gun culture comes in with a deeply problematic, confirmatory myth: guns make me safer. Even if safety were a purely personal concept and not a collective responsibility, a gun is about overpowering threats, not containing or obviating them. Safety as the capacity for violence is rooted in the expectation of violence. And that expectation comes from that same view of the world as dark and dangerous, of other as threat. The behavior of the heavily armed, well-trained police in a Texas school hallway last week should tell us everything we need to know about guns making us safer as they hid to protect themselves from an untrained eighteen year old gunman.

For Republicans and others committed to gun culture, gun rights, and self-interest, their narrow definition of community, of America and their comfort and commitment to the myth and to minority rule work for them and allow them to remain irresponsible for others. They do not want to and are not willing to accept the moral obligation at the root of the civic duty demanded by living in a genuinely democratic nation. To move in this direction, to continue to get better at democracy, we need a broader definition of community. We need a new strategy for getting back into some kind of shared container that includes an abiding faith in each other and a commitment to each other’s thriving. We need a new cultural narrative that elevates our interdependence and that being deeply connected to people and to people different from us, that that difference is exciting and good for all of us. And that our shared moral obligation is a source of joy and opportunity that enriches us and our lives, not just a responsibility. We need to embrace the idea that we share responsibility for each other’s safety or our tradition of violence will remain our present and our future.

People who openly and violently attack their own government and actively endanger children are criminals, but acting like their rival gang is confirmation of their dangerous and illiberal worldview. We cannot win their game — winning their game does not get us where we want to go. Take responsibility for others. Protect people. Make people more free and expand participation and self-determination. Lead even when you fail. Be democratic. It is easier, safer for me to hold on to the idea that these opponents might be suffering. I am not sure if I weren't a straight, white man if I'd be able to. But holding both — that sympathy and that the criminality and the consequences of that suffering cannot be allowed to lead us — is part of how we get better at democracy: by embracing, embodying, and ultimately codifying democratic culture. The alternative is to accept their dark view of humanity and a world of threats and the narrowest possible definition of America and American that pits a shrinking minority against everyone — it’s too unambitious, to beneath what we can be, and too dangerous to accept.

Today, our only hope is to reduce the power of people intent on prioritizing property over people and then to demonstrate the power and possibility of putting people first. We know what to do to make our communities safer (we have dozens of evidence-based policies ready to deploy), and we'll need to do all of these things and more to undo the now decades of loosening and expanding access to guns that has led to a nation with more guns than people and to address all the different kinds of gun violence endemic in our society. But we will never effectively put any of them into practice until more of us are willing to accept the responsibility of civic duty that prioritizes people over property. We have to engage in this conflict of visions as the moral conflict it is. The filibuster, gerrymandering, corporate capture are all deeply anti-democratic features of our minority-rule republic but all downstream of the cult of self and privilege. So we must do all the things: protest, vigil, lobby, argue, run against them, pass whatever large and small measures are possible wherever possible — occupy all the lanes, all the time without rest. But conflict doesn't mean war, and winning doesn't mean overpowering or eliminating opponents. It might demand a slow opening of eyes, a gentle expansion of experience and narrative, and a persuasive injection of new stories that distort our distorted reality. And it may take as long as the distortion took to take hold to undo. No one thing is going to change our America. Yes, all the rules. Yes, all the protests. Yes, new leadership. Yes. But we must also focus on the longer view of the culture that makes the America we want possible.